A Review of What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy

Philippe Sands, an international human rights lawyer, was doing research for a book on the Nuremberg trials, when he met Niklas Frank and Horst von Wächter. Niklas and Horst, both born in the spring of 1939, had known each other as boys. Their fathers were both prominent Nazis all through World War II, and this was the common thread that tied the three men together.

Niklas’s father, Hans Frank, was a highly cultured and educated man. He knew Goethe and Shakespeare. He was the personal lawyer of Adolph Hitler, and then rose to the position of governor general of all of Poland. After the war, he was dubbed The Butcher of Poland. He was hanged at Nuremberg for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Horst’s father, Otto von Wächter, was one of Hans Frank’s deputies. He was named SS Oberfuhrer on Kristallnacht and went on to run the transportation system that moved people from German-occupied cities and ghettos to the concentration camps. After the war, he was indicted of mass murder, but having fled and sought protection from the Vatican, he died in 1949 in Rome. Horst’s parents, both proud Nazis, had named him after Horst Wessel, the erstwhile martyr/mascot of Nazi Germany.

For Sands, a Jew, meeting the two septuagenarians was deeply personal, as a large branch of his family tree – more than 80 of them from one Ukrainian city alone – had been summarily executed under the personal direction of Otto von Wächter. Nevertheless, with much trepidation, he brought the men together to make a documentary about their reflections on their fathers.

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy is loosely structured around Sands’s questioning Niklas and Horst about their attitudes toward their fathers and the crimes they committed. To be sure, Niklas and Horst were mere boys – age six when the war came to an end. Of course they’re not responsible for their fathers’ crimes. But what are their thoughts today, Sands wanted to know, about their fathers?

Two Moral Responses

The short answer to that question for Niklas, who is eager to criticize his father in public settings, is that he unequivocally repudiates his father’s actions. He says that his father deserved to die for what he did. He was raised Catholic, Niklas points out, so he knew right from wrong. Niklas says he himself has peace now about his father because he has acknowledged his father’s crimes.

Horst, on the other hand, has responded quite differently. “I must find the good in my father,” he says. Citing loyalty, Horst intractably resists ascribing any guilt to his father. “I’m very sorry about this,” he says, but the charges against my father are “very general suppositions … all generalizations. … I have so many documents from people who knew him personally, who said he had a decent character.”

When presented with evidence of Otto von Wächter’s command responsibility over tens of thousands of death en masse, Horst replies, “He had no influence. He tried everything he could do to prevent the things that have happened.”

The discussion is civil, but tension mounts over the course of the film. Sands and Niklas want him to condemn the crimes, but Horst excuses, evades, and/or relativizes every charge they present. “The system was something [that we today] can’t imagine,” he says. “Death was so near to everybody. Life was just nothing.” Bad things happen still today everywhere, he says, and “we have no means to stop them. We have to accept them.”

A scene with a similar dynamic takes place in the film Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed, where Ben Stein, also a Jew, visits the Clinic for Forensic Psychiatry/Centre for Social Psychiatry in Hadamar, Germany, where thousands of people deemed unworthy of life were put to death. The curator of the Hadamar museum declines to pronounce any judgment, though, when Ben probes her thoughts about it. “They had purposes,” she said. “I don’t think that it’s my role to tell him something,” she says regarding one of the lead doctors who oversaw the killing.

Ben doesn’t press her. Similarly, in the end Philippe Sands and Niklas Frank give up all hope of getting a moral judgment out of Horst. Clearly, it’s not going to happen, and the film ends with the three men at an impasse, Sands and Niklas on one side and Horst on the other. “I despise him,” Niklas says bitterly, about Horst.

To his credit, Sands displays no animosity toward Horst. He and Niklas just want to hear Horst condemn the crimes. Because, to Philippe Sands at least, those lives were not “just nothing.” They were his family.

The Question of “Ordinary-Looking” Evil

Niklas predicts that Horst – or at least those who live in the same spirit as Horst does – are the seeds of a new Nazism. He may well be right, and I think this is a large part of what motivated Sands and others to produce this film. There is yet evil in our midst. And it can look disturbingly, alarmingly ordinary.

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy, is gripping viewing. How could these men, Sands asked early on, meaning Hans Frank and Otto von Wächter, participate in mass murders by day and then spend an evening with their families at night?

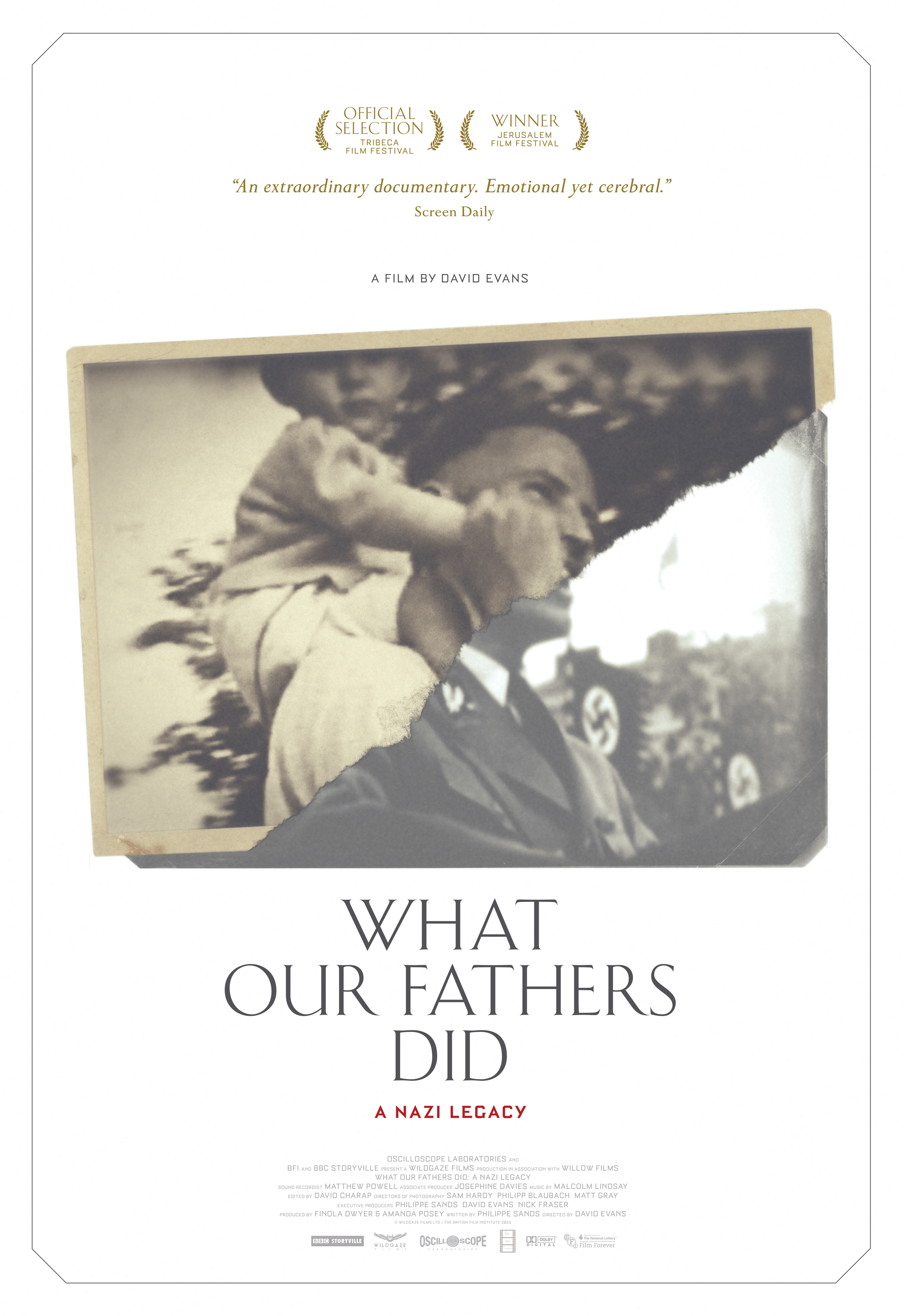

As it turns out, we learn from their sons that they didn’t spend many evenings at home with their families (Niklas says his parents hated each other). We do however get a rare look at some of their home movies and family photos. Viewers with a working moral compass may feel a dark disquiet at the sight because Hans Frank and Otto von Wächter look to all appearances like fine, upstanding citizens, certainly not moral monsters capable of mass murder.

So the question lingers. How could such ordinary looking men be capable of such evil? Watching Horst’s home movies and looking at family photo albums, Sands noted, “felt dirty” to him, as if in some way he was “looking on the inside of horror.”

It’s a poignant observation, for which the film itself provides no answer.

Moral Reality

Only the Judeo-Christian worldview gives us a comprehensive answer to that question. It presents man as created in the image of God but desperately fallen and capable of great evil. It also presents man as a moral being, capable of choosing between good and evil. Some choose to turn toward God, owning their own fallenness. Others choose to turn away. In the end everyone receives what he has chosen.

The biblical worldview also explains that angst Niklas and Sands expressed over Horst’s stubborn denial, that palpable (and right!), gut-level inability to “be okay” with his moral blindness. Human lives are not nothing, and they all know it. Mass murder, even if it is sanctioned (or ordered) by otherwise legitimate governing authorities, is not excusable.

And, no Horst, we do not have to accept it. There is an objective standard of right and wrong to which we are all bound. And we all know it on some level.

This is the gist of what’s called the moral argument for God, which goes like this:

- If God does not exist, objective moral values do not exist.

- Objective moral values do exist.

- Therefore, God exists.

People have attempted to muster arguments for moral relativism, but those who really adhere to it end up excusing great evil.

Horst is a very sad specimen of lost humanity. He could, if he would, still find the good in his father while also condemning his crimes, if he would allow the Moral Lawgiver to set his moral compass. But if he hasn’t by now, it’s hard to see how he ever will. That is a great tragedy.

For the rest of us in the free world, we would do well to watch this film and grapple with the question of objective morality and evil in our midst. Those who refuse to see and identify evil not only allow it to spread unchallenged, but inevitably end up succumbing to it and participating in it.

Related:

- What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy – click here to see the trailer and for information about screenings.

- A Time to Judge: Nazi Germany and the Peril of Moral Weakness

- The Moral Argument for God from Reasonable Faith

Please,as Christians we have the responsibility to seek the truth,wherever it leads us.

Read some revisionist for evidence based facts and literature.

Want some advice where to find it?

I can help you.