Introduction

Introduction

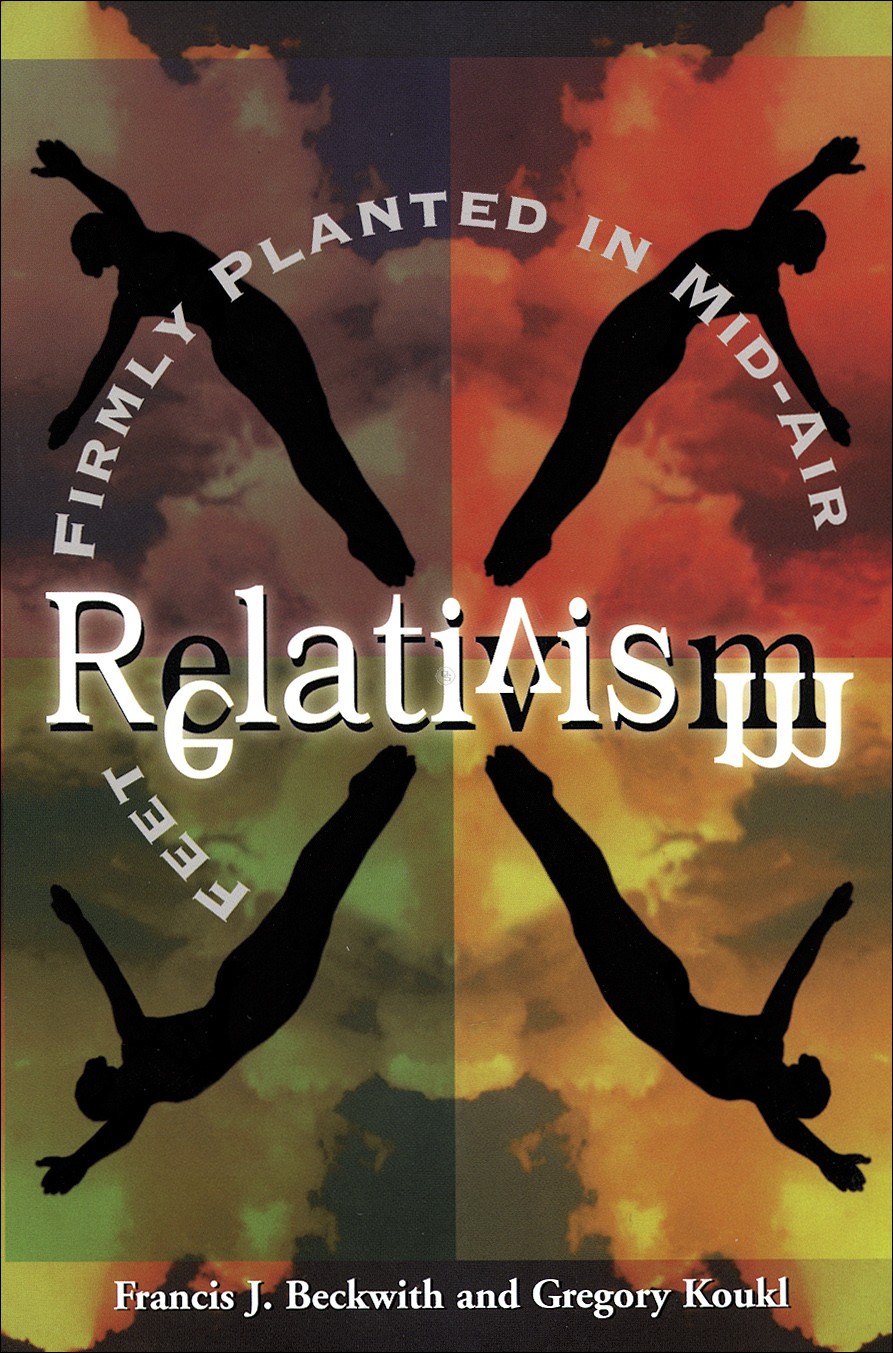

More and more it seems that society and culture are attempting to jettison objective morality in favor of their own moral autonomy. It is a challenge that takes place at both an individual level and a political level. The Christian worldview holds that certain actions and behaviors are right or wrong regardless of who believes or does not believe that they are. Christians need to be able to defend this position in their everyday discussions with friends, family, and coworkers; otherwise, they may cave to the “wisdom of the world.” Greg Koukl and Francis Beckwith wrote Relativism: Feet Firmly Planted in Mid-Air (soft cover, Kindle,GoodReads) precisely with these everyday Christians in mind.

The book is divided into five parts (sixteen chapters) and 170 pages. This review will be a part-by-part review (rather than my usual chapter-by-chapter, due to the short length of some chapters) to provide the reader with a quick summary of what they can expect from the book. This month I will cover Parts 1 and 2. Next month will cover 3, 4, and 5 and my thoughts will conclude the review. While both Koukl and Beckwith are in agreement with all the content in the book, they each were the primary authors of certain parts, so I will refer to them by name (even though both authors are represented).

Part 1: Understanding Relativism (Koukl)

Greg Koukl begins the investigation into moral relativism by identifying it. He provides several examples in society that point to the fact that the idea of objective moral truth is becoming less and less prevalent. He explains that the pursuit of pleasure tends to be the new measure of ethics and that the charge of “intolerance” is the weapon of choice against those who disagree.

To clarify exactly what is being identified he distinguishes between moral “oughts” and rational “oughts.” He explains that both are truths, but only the former warrants correction of the person, while the latter warrants merely correction of the error. He explains the difference between objective truth and subjective truth. Objective truths are grounded outside the individual, while subjective find their foundation in the individual. Objective truths are the same for all people, at all times, in all places, while subjective truths are subject to the ever-changing whim of the individual.

Koukl makes the point that there is no real difference between a moral relativist and one to denies the existence of morality. He also exposes the claim of moral “neutrality” for the myth that it is: that no one is actually neutral if they express an opinion or make a claim about morality. Koukl describes three different types of relativism that pervade our culture:

- Society Does Relativism- Description of anthropological observations of societies

- Society Says Relativism- Prescriptions that are determined by a society

- I Say Relativism- Prescriptions determined by the individual

Part 2: Critiquing Relativism (Koukl)

In the second part Koukl critiques each type of relativism individually then presents challenges against all forms. The idea of “Society Does Relativism” comes from observations of anthropologists. They observe specific behaviors and attempt to conclude a certain moral code from them. However the only thing that can be concluded from these observations is what is, not what should be, so technically it does not even qualify as a moral system.

In contrast, “Society Says Relativism” derives its obligations from the culture, usually the majority or the most powerful party/individual. However, this breaks down in multiple ways. One challenge is the fact that no society can ever stand in judgment of another. If a society decided it was morally obligated to commit genocide against a people-group, no other society could justify defending that people-group on moral grounds- the only defense would be based on that other culture’s accepted obligations. Neither could there ever be moral progress. If no standard exists to aspire to reach, then one cannot determine if a society is progressing, regressing, or stagnating. Without an objective moral standard outside a society, that society’s morality can only change can never be “better” or “worse” than before the change. “I Say Relativism” falls by many of the same critiques, but is made worse because many more individuals must coexist together than societies, thus more opportunities for conflicts are revealed.

Even though he presents a powerful philosophical case against relativism Koukl also argues that morality can be known to be objective by personal intuition. He explains that if one is to necessarily require an evidential case for objective morality that an infinite regress of explanations will result, so one must have some starting point, which can only be known by intuition. Koukl concludes this part of the book, though, with an comparison of societal and individual behaviors that are incompatible with any form of relativism. He demonstrates how moral judgment, the problem of evil, blame, praise, moral progress, and even tolerance are all meaningless if moral relativism is true. He uses the fact that individuals believe these are meaningful as evidence to support the idea that people intuitively know that morality is objective.

Next month’s portion of this review will cover relativism in education and public policy and the authors’ recommended ways to address those who support relativism.