[Somebody’s] Truth about the Universe and How You Fit into It

In the 1980s, David Christian, a 40-ish year-old professor of Russian history at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, became discontent teaching “just the history of one country.” “[N]ot really sure … in a sense, who I am,” he wanted to know about the history of humanity as a whole. “That question forced me back,” he said. “If you want to know about humanity, you have to ask about how humans evolved from primates.” His inquiry continued pressing backward until he was asking about the origins of the earth and then finally of the whole universe. He read widely, synthesized what he found into a course, and began teaching it as “Big History” in 1989.

In the 1980s, David Christian, a 40-ish year-old professor of Russian history at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, became discontent teaching “just the history of one country.” “[N]ot really sure … in a sense, who I am,” he wanted to know about the history of humanity as a whole. “That question forced me back,” he said. “If you want to know about humanity, you have to ask about how humans evolved from primates.” His inquiry continued pressing backward until he was asking about the origins of the earth and then finally of the whole universe. He read widely, synthesized what he found into a course, and began teaching it as “Big History” in 1989.

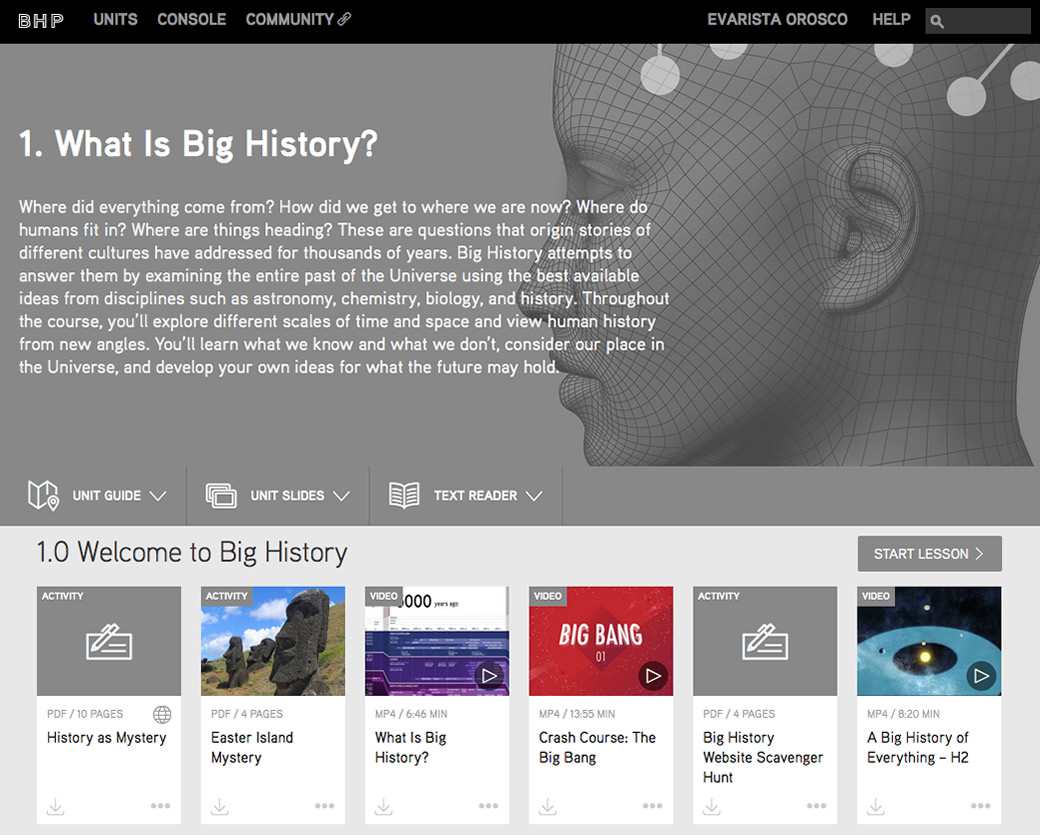

Bill Gates later saw the DVD series and wanted to make it available to more people. He tracked down Christian and the two founded the Big History Project to disseminate Big History globally, beginning with high schools. The resulting 10-unit, 50-lesson course spanning 13.7 billion years of “universe history” went online in late 2013. The project is funded by Gates’s LLC, bgC3 (Bill Gates Catalyst 3), which is described as a think tank, incubator and venture capitalist firm.

Big History is billed as “a true history course … with a goal of helping students understand a historical narrative and ultimately human civilization’s past, present and future.” Christian and Gates speak of it with infectious enthusiasm. “This is my favorite course of all time,” says Gates. It’s very special because “it creates a framework for so many of the things [students] will learn in other courses.” How was the universe created? Why does it work the way it does? Why do we find ourselves on this tiny planet, buzzing with life? What does it mean to be human? These are the question Big History purports to answer. They fascinated Christian from the beginning and motivated him “because they made me feel I was a part of something absolutely huge and quite wondrous.” “By the end of this course,” he says, ”you’ll have surveyed the whole history of the universe. And you’ll know how you fit into it.”

What History?

The question that needs to be asked, though, is, In what sense is this history? When Gates concedes that it “blurs the boundaries between science and geography and history,” he doesn’t go far enough. Take another look at the questions Big History aims to answer:

- How was the universe created?

- Why does it work the way it does?

- Why are we here?

- What does it mean to be human?

These aren’t the questions of science, geography, or history, but of philosophy and religion. Big History purports to be “Universe History,” “Universe History” being the grammatical equivalent of “Russian History” or “Film History.” But that’s not what it is. Big History is a story of the universe, according to a particular metaphysical worldview – the materialist naturalistic, or atheistic one – to be specific.

Big Religion: Now Showing at a School Near You

Big Religion: Now Showing at a School Near You

A broad range of schools are already implementing Big History in the United States and internationally. The project provides all materials and teacher training and offers subsidies to cover additional direct expenses incurred by schools. Given the funding and big names behind it, Big History is sure to be expertly produced, engaging for students, and widely propagated,

But if we take the first definition listed for ‘religion’ on Dictionary.com, “a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the universe,” there is no way to take Big History as anything but an alternative religion. A slickly presented, secular religion, now showing at a school near you.

This article first appeared in Salvo 27, Winter 2013

Religion = belief system, Science = theoretical system. Not the same thing.

A scientific theory is a well-substantiated explanation of some aspect of the natural world that is acquired through the scientific method, and repeatedly confirmed through observation and experimentation. As with most (if not all) forms of scientific knowledge, scientific theories are inductive — that is, they seek to supply strong evidence for but not absolute proof of the truth of the conclusion—and they aim for predictive and explanatory force. As additional scientific evidence is gathered, a scientific theory may be rejected or modified if it does not fit the new empirical findings- in such circumstances, a more accurate theory is then desired. Scientific theories are testable and make falsifiable predictions. (Wikipedia)

Religion is a set of beliefs, science is a set of theories. The two could not be any different. It’s apples and oranges.

(“Secular religion” also makes no sense that’s like saying non-religious religion, which I guess it’s similar to the other paradox of non-belief belief you’ve been discussing…)

Atom Coeur, my honest response to you is pretty much the same as the one above to tildeb. We have different beliefs about beliefs. I really don’t mean to be circuitous. This is the stuff of philosophy – philosophy of science and philosophy of religion, to be specific. People approach the different realms of knowledge according to their own personal worldview choices.

To tie this point back to the post that launched this thread, the makers of The Big History Project are offering answers to questions that fall under the realms of religion and philosophy, not the empirical sciences.

Again sorry to repeat things but there is a vast difference. The “answers” provided by Big History are not dogmatic nor are they presented as beliefs – they are theories (see definition of theory in my previous comment). To be precise Big History is a collection of theories from different sciences which makes it an interdisciplinary science. It would be very dangerous and pretty much defeat the purpose of the scientific method if one would take these theories as beliefs to be followed or answers to spiritual questions. They should always be seen and explicitly presented as non-absolutist, working theories that are actively subject to change, redefinition, interpretation and scrutiny.

I agree that they are completely different epistemologies however they needn’t be mutually exclusive. I think there is a way for both to coexist in a person’s worldview without conflict all the while enriching their spiritual needs and beliefs. Science is not a threat to religion simply because it is not meant to replace it or pose as religion. Religion fulfils needs that science couldn’t possibly fulfil, and science finds solutions to problems that religion couldn’t possibly solve. They are two completely different things with completely different aims and purposes!

pretty much summarised by: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallibilism

“fallibilism consists of being open to new evidence that would contradict some previously held position or belief, and in the recognition that “any claim justified today may need to be revised or withdrawn in light of new evidence, new arguments, and new experiences.” This position is taken for granted in the natural sciences.

In another sense, it refers to the consciousness of “the degree to which our interpretations, valuations, our practices, and traditions are temporally indexed” and subject to (possibly arbitrary) historical flux and change.”

I do not prescribe to metaphysical naturalism (ontology); I prescribe to methodological naturalism (epistemology). In other words, I prescribe to the position that the knowledge quality of claims made about how reality operates means that reality – and not my applied beliefs about it – has the final say. I maintain the position that reality has the right to arbitrate my beliefs about it… and not the other way around (where I empower my beliefs to arbitrate how reality operates). In addition, in order for claims to be presented about reality as if possessing knowledge means that reality – and not my beliefs about it – has arbitrated the claims and it – not my imposed beliefs – offers compelling evidence that the claim can stand independent of any beliefs I may or may not have.

Alright, this is good, tildeb. You have put forth something we can work with:

(1) You do not subscribe to metaphysical naturalism as an overall worldview, and (2) Truth claims should be evaluated by whether or not they conform to reality. At least that’s what I think you said.

I’m going to put forth a truth claim regarding metaphysical reality and invite you to respond to it: God exists.

Now, as a matter of personal belief about metaphysical reality, there are three ways you could respond to that truth claim: (a) I accept it as true and agree. I believe God exists. (b) I reject it as false and disagree. God does not exist. Or, (c) I neither accept nor reject it. I do not know whether God exists or not.

I’m guessing your response to the truth claim, God exists. would be (c). Would I be right?

Not quite. I do not know (the word is missing from ‘c’ but I presume this is what you meant) if any gods exist because I have no compelling evidence adduced from reality to indicate this is probable. Because I have no compelling evidence for the claim, I also recognize that have much compelling evidence against the claim. Therefore, I ascribe very little confidence to the probability that it is true and assign it as highly unlikely. That’s why I can say I don’t believe any gods exist and call myself an atheist. But note the two conditions here: the first condition is a knowledge claim that God exists and so my honest response is that I don’t know this to be the case (and neither do you); the second condition is a belief claim that God exists and so my honest response is that I do not believe (and you do). My belief is justified on the condition of my knowledge and my knowledge is justified on the condition of what reality indicates is probable (that can be demonstrated to be equivalent for everyone everywhere all the time). When we reverse this order and allow belief to determine probability, we remove reality’s role to arbitrate by independent demonstration claims made about it. This leads one to believing in claims that have no necessary link to reality, no necessary link to its demonstrable truth value by reality, and this is exactly what we find in play through beliefs justified by religious faith. That’s how one justifies drinking the Cool-Aid.

You presumed correctly. The word ‘know’ should have been in (c). I corrected it, thank you.

Thanks for the fairly direct and honest answer to my question too. You said honestly that you do not know that God exists. I completely take you at your word.

Then you said this: “(and neither do you)” Tildeb, you do not have knowledge about what I know or don’t know.

I suggest to you that I do, in fact, know that God exists. You can take me at my word or not; that is your choice. But you err when you impose your speculation about what I know onto me.

Here’s my next question, if you’re game to respond with a simple yes or no: If God does exist, do you want to know?

Claiming to know something does not make the claim God exists true. We make such claims all the time about things we believe are true. I though I had clarified that the difference between belief and knowledge rested between the dependent or independent nature of the justification for it. I included the sense that knowledge means explanations we use that are the same for everyone everywhere all the time and can be demonstrated to work. Your knowledge claim about your god existing does not fit this definition; it fits the definition for belief that your god exists. Apples and oranges.

I find theists generally use these terms – belief and knowledge – interchangeably as if they were equivalent. This is a methodological error. Belief is not equivalent to knowledge and this, too, is demonstrable; I believe my sports team will win the championship for a variety of reasons. That belief – and the quality of the reasons I use to make the claim – doesn’t make the claim true, doesn’t turn the claim magically into ‘knowledge’. For that to happen requires reality to inform it… by the team actually winning the championship. My belief – no matter how passionately I may think it is so, no matter how diligent I have been assembling my reasons – does not determine reality; reality does. And knowledge claims ABOUT reality must yield to its final verdict or be nothing more than a belief claim (equivalent not to a knowledge claim but a hypothesis awaiting adjudication).

That’s why I can say with great confidence that your claim about the existence of your god is a belief claim and, as such, cannot be a knowledge claim unless and until you can demonstrate that reality has arbitrated it to be so for everyone everywhere all the time. This you or anyone else cannot show… or it would have already be done… demonstrating how the belief (the hypothesis) transitioned into ubiquitous independently verified and applicable knowledge. That is how I can claim you – like I – do not ‘know’ if any gods or god exist(s).

Put another way, if the claim God exists were true, then it wouldn’t need believers and it most certainly wouldn’t require faith of the religious kind. It would be knowledge, demonstrable, evidential, and available to everyone everywhere from reality.

If God does exist, do I want to know? Sure.

You did make a distinction between belief and knowledge. Certainly the words are sometimes used interchangeably when it might be better to make distinctions. And certainly, claiming to know something does not make the claim true. I agree with you there.

But I don’t agree that your distinction is a hard, inviolable law of epistemology, and I don’t view empirical verification as the sole arbiter of truth claims.

I adhere to a different epistemology than simple empiricism because some things can be known without independent, empirical verification.I have a mind, and so do you. Minds can make evaluations and judgments about truth claims, especially when we’re talking about non-material reality. In fact, your distinction concerning belief and knowledge lacks independent verification or justification. It’s just a bald assertion on your part.

I know that non-material reality exists. I know this because I am conscious of my own existence. Consciousness is one example of non-material reality. So is conscience, I suggest to you that you also know that non-material reality exists, unless you want to tell me you aren’t conscious or don’t have a conscience.

So if we can establish together that we can have knowledge of non-material reality in the commonly used sense of the word knowledge, then we can go on to the next matter, which is the existence of God. If you do want to know, I’ll be happy to offer evidence for your evaluation and judgment.

Bait and switch.

Here’s the bait: I don’t agree that your distinction is a hard, inviolable law of

epistemology…

I never claimed that the distinction between belief and knowledge is a ‘law’ of epistemology. It is a very useful working definition to separate claims informed by belief and claims informed by reality and then reveal why these two approaches are not just quantifiably and qualitatively different in method but can be demonstrated to be different in product. Belief produces claims that are dependent on those beliefs; knowledge produces claims that are independent of beliefs. This difference matters a very great deal when we are talking about claims made of reality. Dependent claims don’t produce independent knowledge; independent claims do. And the product evidence between the two methodological approaches is quite compelling: knowledge claims produce applications, therapies, and technologies that work for everyone everywhere all the time. Belief claims produce… well, you tell me. Where is the equivalency you claim? Show me the equivalency you think is true. I don’t think you can show me compelling evidence that the claim to equivalency between your dependent beliefs and independent knowledge is true because there’s nothing equivalent – no products of belief that work for everyone everywhere all the time – to show. This means the flip side of the belief/knowledge coin is equivalently false: that knowledge claims are just a different kind of religious belief (which was my central criticism of your OP). There remains an important difference bulldozed aside to maintain such a claim for equivalency.

And now here’s the switch: …and I don’t view empirical verification as the sole

arbiter of truth claims.

Notice what’s missing? It has something to do with claims made about reality requiring reality – and not beliefs – to arbitrate them. You skipped this central plank of my criticism entirely – the role reality is allowed to play in claims made about it – and altered it to seem to be about truth claims of any kind (I like the colour green and enjoy limericks) and how you reasonably don’t view empirical verification to be its adjudicator. Neither do I. So this switch doesn’t accomplish its task – to bring belief about reality to be an equivalent method to justifying claims made about it and how it operates.

Yu further the switch to make the claim that there really is a non material reality. Again, the terminology is problematic because what you’re doing is crossing the border between a descriptive reality and a normative reality. A descriptive reality can introduce relationships and patterns between material entities (like brains, for example that produce emergent properties like preferences, humor, and consciousness and create symbolic representations of these with objects in reality – like numbers, logic, morality). A normative reality contains only the material entities themselves (which confuses people to assume such patterns, relationships, and emergent properties are non-material material entities! This leads people to claiming that love is a thing, morality is an object, consciousness is a disembodied entity, and so on. These people have confused the descriptive from the normative in the same way you have confused dependent belief from independent knowledge and assume that the former can be used to justify claims about the latter.

You’re right about your asserted distinction between beliefs and knowledge, and I think I can follow your line of reasoning as far as it goes.

But no, I didn’t skip the central plank of your criticism. My epistemology rests on two presuppositions: (1) There is such a thing as non-material reality. I’m not talking about things that are a matter of opinion like a favorite color. And since you said you didn’t subscribe to metaphysical naturalism, I assumed you believe there is such a thing as well. (2) Human minds are capable of making rational evaluations and judgments about non-material reality.

If you disagree with either of those, then our disagreement lies in our epistemologies. And those are personal choices, not matters to be empirically adjudicated. In a certain sense of the word, I think you can say they are matters of faith.

So I don’t think I’ve done a bait and switch at all. I think we hold different beliefs about knowledge. I’m honestly not trying to be circuitous here. This is really what I think is going on between you and me.

There is such a thing as non-material reality.

You say this is a matter of epistemology. Fine. Then please demonstrate how you know this (not why you believe it… because the claim is not about a subjective belief but one that is presented as if independent of any beliefs you or I may hold about it) from evidence adduced from reality, please.

I’ll be happy to answer that question, but I’d like to know where you’re coming from first. Do you agree that there is such a thing as non-material reality? or do you disagree? You personally, whether you think of it as a belief or knowledge.

I’m really not looking for a complicated thesis-type answer. Just a conversational yes or no that tells me where you’re coming from.

I think there is exactly the same problem asserting a non-material material as there is with a non-belief belief… an indication that something in the reasoning has gone badly askew. The use of the term ‘reality’ to replace the second ‘material’ indicates where the confusion lies, namely that you claim there is something that is not a thing, which I suspect indicates it cannot be available to both of us, hence cannot be knowledge about reality but about a belief in place of it and/or imposed on it.

Whatever the ‘non-thing’ is that you assert is real (a part of reality) must be accessible to anyone to be knowledge, and when you move away from its demonstrable existence then you must move away from knowledge and into an inappropriate epistemology. That’s why asked you how (there’s the epistemology, the method of inquiry, in action) do you know this (there’s the heart of the claim you’re making, that you DO know this)?

Unless I can be shown otherwise by evidence adduced from reality, I do not think we can know anything about a non-material reality in reality.

tildb, I’m just using plain, colloquial English. I was giving you credit for being able to follow what I was saying.

To respond to your question about evidence for non-material reality, please consider this: We are having a conversation about ideas. We are using words, organized to convey information and concepts. Ideas, concepts, words, etc., all of these organized in a specific way to communicate information. These are all examples of non-material reality. If ideas, language, words, information are not real in your view, then you are left occupying the truly absurd position of saying things in this conversation that you don’t believe or know to exist or mean anything.

Here is my recommendation to you: You have been hanging around the CAA for quite some time, now. You function in a way as a resident critic. That’s acceptable. We who write here put these posts out for people to read and respond to. At this point, you have done a lot of responding that amounts to quibbling objections. If you want to show some good faith in becoming an intellectually honest critic, I recommend you take the time and effort to try to understand the CAA authors’ point of view. Understanding your adversary’s point of view is part of legitimate literary criticism, so you can step up your game by doing that.

To do that, I recommend you read the Bible. You may not agree with what we believe about it (which you can review in the CAA Statement of Faith), but it is the foundational text of Christianity and the CAA. If you will make an honest, good faith endeavor to understand where we’re coming from, then I’ll continue to respond to your questions as if they’re good faith inquiries.

If you won’t do that, then I’ll conclude this thread with you by reiterating that we have different beliefs about knowledge, wish you well, and leave it at that.

tildeb, I’m using normal, conversation language assuming that you have the ability to follow my train of thought.

If you don’t believe that the very concepts and ideas that we’re discussing are real in any knowable sense, then that leaves you in the absurd position of making statements about concepts you don’t believe actually exist.

Here’s my invitation to you: You have been hanging out at the CAA for quite some time, objecting to posts. You’ve become something of a resident critic. I invite you to step up to the level of an intellectually honest critic and attempt to understand your adversaries’ point of view. From the CAA Statement of Faith you can see that our beliefs are based on the Bible. Read it – the Bible, I mean. You may not agree with it, but at this point, you can either continue to criticize with no basis or you can seek to understand our point of view. In the interest of honest inquiry and good-faith dialogue, I recommend the latter.

If you won’t do that, I can only leave you this: We have different beliefs about knowledge.

tildb, I’m just using plain, colloquial English. I was giving you credit for being able to follow what I was saying.

To respond to your question about evidence for non-material reality, please consider this: We are having a conversation about ideas. We are using words, organized to convey information and concepts. Ideas, concepts, words, etc., all of these organized in a specific way to communicate information. These are all examples of non-material reality. If ideas, language, words, information are not real in your view, then you are left occupying the truly absurd position of saying things in this conversation that you don’t believe or know to exist or mean anything.

Here is my recommendation to you: You have been hanging around the CAA for quite some time, now. You function in a way as a resident critic. That’s acceptable. We who write here put these posts out for people to read and respond to. At this point, you have done a lot of responding that amounts to quibbling objections. If you want to show some good faith in becoming an intellectually honest critic, I recommend you take the time and effort to try to understand the CAA authors’ point of view. Understanding your adversary’s point of view is part of legitimate literary criticism, so you can step up your game by doing that.

To do that, I recommend you read the Bible. You may not agree with what we believe about it (which you can review in the CAA Statement of Faith), but it is the foundational text of Christianity and the CAA. If you will make an honest, good faith endeavor to understand where we’re coming from, then I’ll continue to respond to your questions as if they’re good faith inquiries.

If you won’t do that, then I’ll conclude this thread with you by reiterating that we have different beliefs about knowledge, wish you well, and leave it at that.

*** by the way: I posted this reply 5 days ago. For some reason, WordPress marked it as spam. I’m reposting now.

Well, a bunch of things here, so I apologize for the length but I think it’s necessary.

Firstly, rest assured that I have not just read the bible; I have submitted many academically approved essays about it for an undergraduate four year honour’s degree (you can tell my British English by the addition of the ‘u’ in such a word as ‘honour’) comparing and contrasting four versions in use today… eventually with a focus on Job. The differences are not trivial. I also have completed a very long reading list concerning the church fathers and the combination of ‘natural philosophy’ and metaphysical foundations for their writings. (Of interest may be the approach used by my multidisciplinary faculty outside of the 8 term papers, two major papers with 12 respected annotations, and a thesis paper with a minimum of 25 respected annotations and a defense before a board, to read a required source weekly and then have to come up with two things for each: an important question about the major theme contained in each of 24 major readings per term, and an explanation why the question is important… to then be presented not only in written form for evaluation but in seminar for wider discussion. Note the emphasis is on learning how to ask really good questions rather than producing or reproducing acceptable and/or stock answers… something I’ve carried forward into all my pursuits.)

My theological study does not end here; I have written extensively about Aquinas and the evolution of the christian faith over the Middle Ages by various authors. I have a masters thesis awarded based on my work about Galileo. It is on this knowledge – adapted to show how and why Galileo dismantled the necessary justification for both the natural philosophy and metaphysics of all faith-based belief – that I recognize why something like a Masters of Divinity is not a similar academic grounding representing expertise in critical thought about theology; it is theological skills training similar to that produced here in Canada through the attainment of a college diploma in a trade.

On this educational basis, I understand apologetics to be (at its heart) a sales job apologizing and excusing for the vast inconsistencies inherent in the ontology of faith-based beliefs… in effect, a product being sold to people that does not come with appropriate warning labels for the consumer/student/believer. My criticisms of (and sometimes compliments for) various writings found here are to do just this: to point out methodological problems that lead people to overstate faith-based beliefs as if they were evidence-adduced beliefs… beliefs justified by religious faith misrepresented as belief justified by reality.

The idea for dualism that you must assume to justify a belief in a non-material reality necessary for the idea of an everlasting soul, of a transdimensional invisible non material driver for our consciousness, is many thousands of years old and has zero evidence adduced from reality to inform it. Again, the ontology of the belief – that there really is a separate and distinct agency each of us possesses for consciousness independent of the brains that produce it, and therefore not subject to reality’s degrading effect on it – comes about only when a specific methodology is allowed – that faith-based belief can be (and must be) accepted to be a sufficient justification without requiring reality to arbitrate it.

For example, you suggest a ‘non-material reality’ can be shown to exist by our ‘non material’ communication. My standard question I ask of all claims is, “Is this claim true and how can we know?”

Well, if we want to question how much of a role a material reality plays in what you consider a ‘non-material’ reality, namely, communication of ideas and concepts – can we still claim that communication of these supposedly independent things called ‘ideas’ and ‘concepts’ can occur? We can do this by a process of elimination. Let’s try and see where we end up.

If we first eliminate stuff in reality that has independent properties of mass, eliminate sounds that represent mutually understood meaning about this stuff in reality, eliminate the physical symbols we use that represent mutually understood meaning for the sounds we use in English, eliminate the machines that receive our individual mechanical input creating those symbols, eliminate the physical transmission of those symbols over distance, what do we have left? Well, we have the form of language that both of us use – the grammar and syntax and semantics – but in order for both of us to know the same knowledge about how to present our ideas and concepts, we have to have been taught by another agency how to use a common form. Now we have to eliminate this common form because of its material presentation. Of course, the final thing to eliminate are the physical brains each of us possesses to accomplish any of these physical (including chemical) tasks.

What do we have left of this ‘non-material’ reality you say exists represented by ideas and concepts? Again, I think you have confused descriptive words (like ‘ideas’ and ‘concepts’) for normative things that exist independently of reality. I don’t think they do exist in any way that is supported by evidence adduced from the reality we share. I think you have to claim they exist by insisting that reality doesn’t get to arbitrate it… that your belief alone is sufficient to establish their existence. Without the material world, these ‘things’ – ideas and concepts’ – lose not just all meaning as independent terms but any means available to us to know anything at all about them.

Now here’s the kicker; your belief alone IS sufficient… as long as you represent it honestly as the faith-based belief it really is (a claim about your BELIEF and not about reality). My criticism is when such beliefs are misrepresented to be a knowledge claim about REALITY.

This difference is crucial to appreciate… and failure to appreciate why this matters so much is the root cause of the problems of incompatibility between the epistemology of a reality-based ontology and an epistemology of a faith-based ontology. By that I mean the problems created by the assertions of incompatible claims made about reality that are in conflict with evidence adduced from it. In the case of apologetics, such fundamental incompatibilites are very often the source material used for article after article after article that makes claims about reality that are immune from its arbitration and then sold to people as if they are. (ie big history as an alternative religion). Nowhere is this confusion more divisive than over issues like creationism and dualism, which are two primary issues sold to people as if they are evidence-adduced claims from reality when, upon closer examination, these claims inevitably reveal faith-based belief in action. Criticizing this kind of failure of honesty by apologetic writers is a necessary task people of faith far too rarely exercise.

tildeb, we have different beliefs about knowledge. Apology for the length accepted, but I don’t think the lengthy explanation of a bunch of things (I followed what you meant by “things” there) was necessary. You believe one way about reality and knowledge claims. I believe another.

It’s a curiosity that with all those credentials, you hang out in a web community you disagree with criticizing under a pseudonym. You’re welcome to continue to do so, but we’ve reached an impasse.

We can believe whatever we want but we’re not being honest if we present these beliefs as being something they’re not, something that can be known independent of our personal preferences to believe this or that, beliefs lacking equivalent knowledge, that something believed should have an equivalent voice to knowledge arrived at by reality’s arbitration of it, that an understanding of reality that seems to be the same for everyone everywhere all the time regardless of contrary beliefs personally empowered means something more than what an individual may prefer to believe, that something so believed should have an equivalent or even superior voice in education, medicine, defense, governance, public policy, law, and so on.

When personal beliefs cross the border that properly bounds them to the personal and disguises them as equivalent knowledge claims in order to cause detrimental effect in the public domain, then we’re no longer dealing with a difference of opinion; we’re dealing with whether or not we – both of us – are more concerned with what’s true and knowable than passing off our opinions as if they were knowledge. Retreating behind the notion that it’s okay to hold incompatible personal beliefs with adduced knowledge and that these ill-informed beliefs should be as influential in the public domain is a failure to differentiate what’s true and knowable from delusion… a very real difference in effect that is not just a difference of opinion but a difference that threatens the health and welfare and autonomy of others. The false equivalency undermines the recognition of our shared human dignity that each of us requires from others only if we are willing to apply the same to others.

For example, many people hold the opinion that their belief about the dangers of vaccines are equivalent to what’s true and knowable. Same epistemology, same ontology as that produced by religious belief: faith-based belief substituted for knowledge-based belief. This method you approve (in order to exempt your religious beliefs from reality’s arbitration of them) is identical: the difference in effect threatens your life unnecessarily, threatens your life and the lives of your children and neighbours and friends and coworkers, all put in very real and increased danger – real danger independent of our beliefs because germs and viruses don’t discriminate between the deserving and the undeserving – by people who think that their belief divorced from the reality it pretends to describe is equivalent to a legitimate difference of opinion. It’s not opinion; it’s a very real difference in respect for medicine, respect for public health, respect for life and the dangers that threaten it. It matters far more than the hand waving that assigns these very real differences of effect aside as if they, too, are matters of opinion when they are not in order to privilege faith-based belief.

It’s simply not worth the cost… for those who care about what’s true and knowable and the wisdom to respect it more than the claims of pious faith-based belief contrary to and incompatible with knowledge.

Thank you tildeb for those many words expressing your personal belief about what can be known. I happen to hold a different belief about what can be known. In other words, you and I practice different personal epistemologies, or, as I have already noted, we have different beliefs about knowledge.

I can be at peace with that – with having identified the point of disagreement and its corresponding impasse – and wish you well. It seems you don’t have the same peace about the impasse.

At this point, I can only (again) wish you well and note that It appears you can’t be at peace without insisting I accept your belief about knowledge. The reason I think that is because you keep insisting that your belief about knowledge applies to me. I wonder if you’ve ever pondered the reason for that.

But if we take the first definition listed for ‘religion’ on Dictionary.com,

“a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the

universe,” there is no way to take Big History as anything but an alternative religion.A slickly presented, secular religion, now showing at a school near you.

Note the boldface: the explanations adduced from reality about the history of the world using our best available method of inquiry are not equivalent beliefs as those that inform the central, and often conflicting, tenets of religions. You have conflated the two different meanings of belief – faith in the religious sense and justified explanation in the scientific sense – to present your conclusion as reasonable. It isn’t. It’s badly confused.

The combination of applying physics, chemistry, and biology to inform astronomy, geology, and the life sciences to adduce how things have come to be as they are is not another kind of religion by any definition of the term; your conclusion that it is an ‘alternative’ kind of religion – a secular kind – is not just wrong but intentionally misleading… unless you commonly refer to things like your cell phone as a ‘secular’ cell phone, your food prepared from a ‘secular’ recipe, your car a ‘secular’ automobile, and so on. I don;t think you do this at all because it makes no sense. There are no such things as a ‘religious’ cellphones, recipes, or automobiles and to pretend there are equivalent kinds is misleading. The term you apply to Big History as in which you use apply the name ‘secular’ is as equivalently misleading and just as absent as the religious products of justified beliefs we call applications, therapies, and technologies based on explanations similarly adduced from reality. Your religious beliefs are in a separate category entirely.

tildeb, you have objected to several of my posts on here. I’m glad to know you’re still hanging around and reading them. Thank you.

We quickly arrive at the same impasse each time. It is this: Your objections are based on a prior commitment to metaphysical naturalism. (See here for the most recent discussion) I do not adhere to metaphysical naturalism.

I don’t know whether you believe metaphysical naturalism is true in the religious sense or true in the scientific sense. I wonder if you know. If you’d like to make a reasoned, evidential case for why you believe metaphysical naturalism is the true nature of reality, please do. Consider this an open invitation.

You continue to deflect my criticism away from its target – a belief you demonstrate to hold that is factually incorrect – and insert that the ‘problem’ is with me, derived from a philosophical position I hold.

Is this true?

In our last exchange you claimed that non belief was another kind of belief. I pointed out that this was factually incorrect. You maintain the position still without considering what this torture of language means: being bald is another kind of hair style, not collecting stamps another kind of hobby, a non car another kind of car. Allowing for this position tortures language into meaning what it does not: being bald is NOT another kind of hair style but a lack of any style of hair whatsoever, not collecting stamps the absence of a stamp collecting hobby entirely, a non car NOT a car at all. This problem is language problem and yours alone; I’m simply pointing out why correcting it matters: for clarity of meaning. Again, atheism means a lack of belief in gods or a god and insisting that this is another kind of religious belief is factually incorrect; it is a LACK of a similar kind of belief held by the religious and not – as you continue to maintain – a similar kind but different held by the religious. This is not a philosophical difference between us or one that I own: it is a mistake in language you continue to use in order for you to misrepresent what atheists actually believe in the service of presenting a lack of belief as some kind of equivalent kind of belief. This equivalency is simply not true. It is factually wrong. And it is owned and exercised entirely by you. WE don’t arrive at an impasse; you START your exchange by asserting something that isn’t true and then build a case based on it. I point out the problem – of why this incorrect premise skews your conclusion – and you reformat that to be a philosophical difference. Bunk. Any ‘philosophical differences’ we may have have nothing whatsoever to do with the error you continue to make empowering this problematic premise I’ve pointed out; this new assertion about philosophical differences is nothing more that a deflection, a tactic to avoid having to face up to why my criticism is not just true but matters to the quality of your conclusions.