“The conception of the objective reality of the elementary particles has evaporated not into the cloud of some new reality concept, but into the transparent clarity of mathematics that represents no longer the behavior of the particles but our knowledge of this behavior.” (W. Heisenberg, 1958) [1]

In this post, I want to focus on the phenomenon of consciousness in respect to quantum mechanics. More specifically stated, recent 20th-century perspectives on the role of the perceptual mind within quantum mechanics. As Varadaja V. Raman writes in his essay in The Journal of Cosmology (2009), “The disembodied soul goes elsewhere, perhaps to a realm transcending space and time. This view of the soul is satisfactory in explaining the phenomenon of dynamic life and inert death at a subjective level but it does not constitute a scientific theory” [2].

Varadaja Raman’s statement can be seen as an interesting pretext in relation to certain discussions regarding philosophical under-linings of the physical universe; however, although Raman here is discussing certain theories applied to the phenomenon of consciousness (e.g., quantum mechanical consciousness, evolutionary, neuroscientific, etc.), Hans Reichenbach (1958) shows how philosophical problems might have their interest in scientific questions by using Euclid’s geometric system as an example:

The problem of demonstrability of a science was solved by Euclid in so far as he had reduced the science to a system of axioms. But now arose the epistemological question how to justify the truth of those first assumptions. If the certainty of the axioms was transferred to the derived theorems by means of the system of logical concatenations, the problem of the truth of this involved construction was transferred, conversely, to the axioms. It is precisely the assertion of the truth of the axioms which epitomizes the problem of scientific knowledge, once the connection between axioms and theorems has been carried through. [3]

Therefore, as even seen throughout the course of his book, philosophy has some degree of relevance to questions regarding the physical universe [4]. As Bernard d’Espagnat (006) once said, “Great philosophical riddles lie at the core of present-day physics” [5]. However, the particular interest I have in that matter is how our own perceptual abilities and quantum mechanics has shifted our understanding of materialistic explanations “from the atom up” to the mind having some role in the discussion (if not an ultimate role – the question of course being “how ultimate?”).

Mindful Primer

In respect to literature regarding this question of consciousness and quantum mechanics, a lot of philosophers and physicists in the past few months have really sparked quite the interest in me to question the more fundamental philosophical questions regarding the universe. For instance, is mind fundamental to the universe? Is there something more fundamental than space-time that might actually underlie it? Are there anthropic properties inherent within our universe that would challenge certain evolutionary cosmogonic models? These questions and more akin to them are not particularly what I wish to address, but rather the role of the mind in respect to quantum mechanics. Showing the relationship – or interest – between the two I believe would constitute some relevant critique regarding materialistic interpretations of consciousness.

For now, consider a relevant problem for our discussion to be this: If quantum mechanics is universally correct (and we might like to think so), then we should be able to apply it to the whole universe in order to find its wave function [6]. In doing so, we could see which events are probable and which ones are not. However, certain paradoxes seem to emerge (Linde, 2004) once we attempt to do so. For example, the Wheeler-Dewitt equation (or, the Shrödinger equation [7] for the wave function of the universe) has a function that doesn’t depend on time – therefore, the evolution of the universe in appeal to its wave function would show that the universe doesn’t change in time.

I was interested by Andrei Linde’s (2004) comment on this subject when he said that “we do not actually ask why the universe as a whole is evolving. We are just trying to understand our own experimental data. Thus, a more precisely formulated question is why do we see the universe evolving in time in a given way” [8] Linde goes on to say from here:

Most of the time, when discussing quantum cosmology, one can remain entirely within the bounds set by purely physical categories, regarding an observer simply as an automaton, and not dealing with questions of whether he/she/it has consciousness or feels anything during the process of observation. This limitation is harmless for many practical purposes. But we cannot rule out the possibility that carefully avoiding the concept of consciousness in quantum cosmology may lead to an artificial narrowing of our outlook. [9]

This is marvelously understood in respect to previous 20th-century commitments to a mechanistic understanding of the universe. As Henry P. Stapp (2009) recognized in his essay “Quantum Reality and Mind”: ” The dynamical laws of classical physics are formulated wholly in terms of physically described variables: in terms of the quantities that Descartes identified as elements of “res extensa”. Descartes’ complementary psychologically described things, the elements of his “res cogitans”, were left completely out: there is, in the causal dynamics of classical physics, no hint of their existence” [10].

Thus, our own mental realities have the ability to know about certain physically described properties but have no baring so as to affect them in any way – therefore leaving man as a “detached observer.” However, “Quantum physics revealed an inevitable interaction between observer and observed in the microcosm. Thus, human consciousness entered the realm of physics” [11]. Henry Stapp makes a notable comment in respect to this shift of thought:

In view of this fundamental re-entry of mind into basic physics, it is nigh on incomprehensible that so few philosophers and non-physicist scientists entertain today, more than eight decades after the downfall of classical physics, the idea that the physicalist conception of nature, based on the invalidated classical physical theory, might be profoundly wrong in ways highly relevant to the mind-matter problem. [12]

Although it surely could be expounded upon in other articles, I personally would advocate Stapp’s position regarding a dualistic account of quantum mechanics (“Von Neumann’s Dualistic Quantum Mechanics”), since in my opinion it has the best account of the ontological character of the physical reality in quantum mechanics and the mental reality’s relevance with the physical (idealistic theories in my opinion are under the same fault as Berkeley’s system, and materialistic theories are just inadequate; so, dualism I think makes the best case).

What Have We Learned?

Materialism understood in the framework of physics fails once we understand the quantum association of the “observer.” Once we integrate certain Aristotelian terms in respect to the ontological character of the physical reality in quantum mechanics (i.e., “potentia” and “actual”), we see that physical reality has the ontological character of potentia – “As such, it is more mind-like than matter-like in character” [13]. Therefore, mental realities cannot be fully revoked under the umbrella of materialism in quantum mechanics.

____________________

Notes:

- [1] Werner Heisenberg, The Representation of Nature in Contemporary Physics. Daedalus, 87 (summer), 95-108.

- [2] Varadaja V. Raman, Four Perspectives on Consciousness. Journal of Cosmology (2009, vol. 3) p. 558

- [3] Hans Reichenbach, The Philosophy of Space and Time, trans. Maria Reichenbach and John Freud (Dover Books: 1958) pp. 1-2

- [4] I would also see Reichenbach’s chapter on “The Difference Between Space and Time” (p. 109) for more of what I mean on this subject. For instance, the first sentence reads, “Philosophy of science has examined the problems of time much less than the problems of space.” Further down he explains that whereas space could partnered up with a Euclidean-geometric example, time can’t really have the same courtesy (cf. Contrasted from previous discussions on space, Reichenbach writes that “it is impossible to distinguish between straightness and curvature” regarding questions of time). Reichenbach thence finishes: “Thus time lacks, because of its one-dimensionality, all those problems which have led to the philosophical analysis of the problems of space.” (p. 109)

- [5] Bernard d’Espagnat, On Physics and Philosophy (Princeton University Press: 2006) p. 2

- [6] In quantum mechanics, with an integrated principle known as the uncertainty principle, particles do not have “definitively stated” positions or velocities, but rather by states that can be represented by what is known as a wave function. According to Hawking (2001), “A wave function is a number at each point of space that gives the probability that the particle is to be found at that position” (Universe in a Nutshell, p. 106).

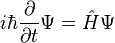

- [7] The Shrödinger equation being (taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schr%C3%B6dinger_equation):

This equation tells us the rate at which the wave function changes through time (see Hawking 2001, p. 107-110). Subhash Kak (2009) also makes the interesting statement that “while the evolution of the quantum state is deterministic (given by the Shrödinger equation) its observation results in a collapse of the state to one of its components in a probabilistic manner.” (See Penrose 2009, pp. 4-5).

- [8] Andrei Linde, quoted from The Mystery of Existence, ed. John Leslie and Robert Lawrence Kuhn (Wiley-Blackwell: 2013) p. 162

- [9] Ibid.

- [10] Henry P. Stapp, quoted from Quantum Physics of Consciousness, ed. Roger Penrose (Cosmology Science Publishers: 2009) p. 17

- [11] Varadaja Raman (2009), from Quantum Physics of Consciousness, p. 89-90 – emphasis mine.

- [12] Henry Stapp (2009), p. 19

- [13] Stapp (2009), p. 20

“Materialism understood in the framework of physics fails once we understand the quantum association of the “observer.””

That’s not true, there are interpretations of QM compatible with modified forms of materialism.

To my mind the existence of subjectivity is a far more cogent argument http://lotharlorraine.wordpress.com/category/qualia/

Friendly greetings from Europe.

Lothars Sohn – Lothar’s son

http://lotharlorraine.wordpress.com