A Review of The Grace Effect: How the Power of One Life Can Reverse the Corruption of Unbelief by Larry Alex Taunton

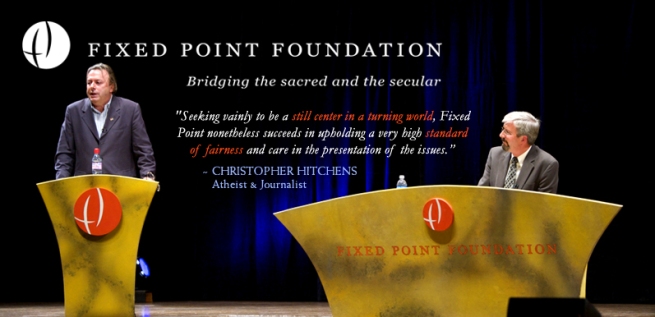

Larry Taunton takes ideas seriously. The Founder and Executive Director of Fixed Point Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to the public defense of the Christian faith, Taunton has personally engaged some of Christianity’s most imposing antagonists. The Grace Effect opens with Taunton and Christopher Hitchens in a restaurant debating Hitchens’s insistence that the world would be a better place without Christianity. Taunton meets Hitchens’s arguments just fine, but he only relates the scene to set the stage for his real rejoinder, who lives, breathes, and transcends mere dialectics.

Larry Taunton takes ideas seriously. The Founder and Executive Director of Fixed Point Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to the public defense of the Christian faith, Taunton has personally engaged some of Christianity’s most imposing antagonists. The Grace Effect opens with Taunton and Christopher Hitchens in a restaurant debating Hitchens’s insistence that the world would be a better place without Christianity. Taunton meets Hitchens’s arguments just fine, but he only relates the scene to set the stage for his real rejoinder, who lives, breathes, and transcends mere dialectics.

Sasha survived Odessa Orphanage #17 with her sweetness of soul intact until age ten, at which point Larry and the Taunton family arrived in Ukraine to adopt her. The odyssey, which forms the bulk of the narrative and which Taunton relates with remarkably kind wit, brings him square up against the institutionalized corruption, iron-souled indifference, and wholesale societal decay that have been the inexorable constants of Sasha’s life up to this point. Some say the region suffers from a “Communist hangover,” but that doesn’t fully capture the social ruin. The human catastrophe of today’s former Soviet bloc was neither self-inflicted nor short-lived, and, as inevitably happens, it’s the children who take the worst of it. The effects are legion:

Dehumanization. Life is cheap, people are expendable, and one of the basest of human inclinations – the impulse to “lord it over another’ – mucks up everything, as evidenced by the ubiquitous tendency of officials to make people wait, as a petty expression of power, simply because they can. The entire system deems people unworthy, and orphans unworthy in the extreme. Worse, the indifference is often papered over by a veneer of self-righteousness. The conditions in which Sasha lived “had all the charm of a chicken house,” Taunton notes wryly, after relating his first meeting with the Adoption Inspector, who’d grilled him on the size and features of the home to which he would be transferring her charge.

Corruption. The apparatus by which people’s very lives are determined runs on bribery. Brief negotiations accompanied by “gifts” move paperwork from stack to stack. On a national level, what this adds up to is a society governed by jungle law, only the jungle has evolved into cobbled, institutional compartments. “In retrospect,” Taunton writes, “I would have preferred crime of the organized type. Then, at least, the process might have been efficient.”

Despondency. Taunton quotes a Soviet era proverb that captures the aimlessness of a culture stumbling along, giving “nauseating obeisance” to the state because it knows no other way, “We dig iron ore from the ground to make steel to make big machines that dig iron from the ground, to make steel to make big machines …” Such is the foggy milieu of a national life bereft of Christian leavening.

The “grace effect,” writes Taunton, “is an observable phenomenon – that life is demonstrably better where authentic Christianity flourishes.” Conversely, where Christianity is suppressed, grace dries up. Taunton’s greatest service, aside from rescuing Sasha out of this dystopia, is that he draws this connection between the atheism underlying socialism and the exorbitant toll it exacts on real people.

Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote, “Socialism is … before all things the atheistic question, … the question of the tower of Babel built without God, not to mount to Heaven from earth, but to set up Heaven on earth.” Compared to the Eastern European orphanage archipelago, it is the “Christianized” West that is Heaven on earth.

Ideas have consequences. Just ask Sasha.

This article first appeared in Salvo 21, Summer 2012.