This post is focused on two terms used in discussions about the history and origins of life. The terms “species” and “speciation” are used extensively to demonstrate that modern evolutionary theory, neo-Darwinism (a.k.a. “molecules to men” via natural processes alone) is a fact. Similar to the previous post I would like to inoculate the lay reader from being bullied by the usage of these terms. I can’t possibly give this a thorough treatment, but I hope to arm you with some questions and smidgeon of skepticism. I intend to do this in two ways. First, I want to define the terms, describe their history, and how they are used in neo-Darwinian circles. Second, I want to offer some thoughts about how “species” is used in the field of paleontology.

To begin with, let’s put the term “species” into is proper context. It is the lowest (or most specific) category within the taxonomic system[1] originally created by Carolus Linnaeus.

For example, dogs are classified in the following manner:

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Carnivora |

| Family | Canidae |

| Genus | Canis |

| Species | Lupus, Canis lupus, or Canis Familiaris |

It is important to note that with all different sizes, shapes and temperaments of dogs in the world, they are all merely breeds within a single species. So what exactly is a species? The standard biological definition is a “reproductively isolated population.” This is one reason all dogs are the same species, while there are some significant mechanical and behavioral differences, the reproductive cells from any two dogs can be combined to create a viable offspring.

The second term, speciation, is an invention of the early 20th century. It simply refers to the creation of a distinct species. In essence, the title of Darwin’s seminal work, “On the Origin of Species,” could have been “On Speciation” or “On the Cause of Speciation.” It is important to camp here for a moment and focus on a key feature of the rhetoric Darwin used to argue for his theory. He drew the attention of his audience to the extensive success of animal husbandry and dog breeding. He assumed a Malthusian view[2] of nature, and asserted that such extreme pressures to survive combined with the timeframe available to nature would cause far more dramatic changes than Man had created in just a few hundred years. In other words, without knowing anything about the underlying mechanism that caused the variations between dog breeds, Darwin extrapolated (assumed) that this mechanism (properly motivated and given adequate time) could explain the development of all animal life.

The second term, speciation, is an invention of the early 20th century. It simply refers to the creation of a distinct species. In essence, the title of Darwin’s seminal work, “On the Origin of Species,” could have been “On Speciation” or “On the Cause of Speciation.” It is important to camp here for a moment and focus on a key feature of the rhetoric Darwin used to argue for his theory. He drew the attention of his audience to the extensive success of animal husbandry and dog breeding. He assumed a Malthusian view[2] of nature, and asserted that such extreme pressures to survive combined with the timeframe available to nature would cause far more dramatic changes than Man had created in just a few hundred years. In other words, without knowing anything about the underlying mechanism that caused the variations between dog breeds, Darwin extrapolated (assumed) that this mechanism (properly motivated and given adequate time) could explain the development of all animal life.

Today, with the vast amounts of observational data from the natural world and the extensive research done on fruit flies and bacteria (to name just two examples), a bona fide example of speciation has yet to be observed.[3] Darwin’s extrapolation, the cornerstone of his theory, remains an assumption.

Now in truth, the above paragraph is open to some debate. There are in fact skeptics of neo-Darwinism that would contend that speciation is possible and has simply not yet been observed. Examples of speciation, if they exist, demonstrate trivial change in the respective organisms. The new “reproductively isolated populations” may refuse to interbreed due to some minor behavioral or physiological change. However such examples fall far short of demonstrating how birds are descended from dinosaurs or how whales developed from land mammals.

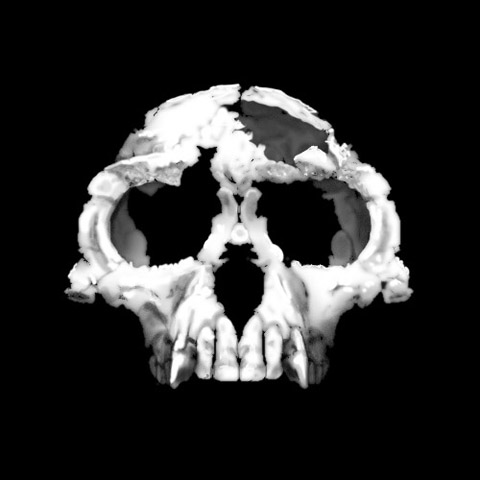

At this point I would like to shift gears from how the word species is used in our observations of living organisms to how it is used in the field of paleontology (the study of ancient or fossilized remains of plants and animals). Paleoanthropologists study the history of man via fossilized bones found all over the world. There are aspects of how this field treats hominid[4] fossil remains that are I think are germane to this post.

First, there is scarcity of evidence. Fossil evidence is scarce in two ways. First, the vast majority of the remains found are confined to portions of the skull. There are examples of “post cranial remains,” but they are more the exception than the rule.

Second, almost every new find is considered a new species. From finds like “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis, where 40% of a skeleton was found) to “Ardi” (Ardipithecus ramidus, mostly known by jaw fragments), nearly every hominid fossil has the potential to be called a new species. This is simply how the discipline is practiced. These scientists work very hard to analyze and distinguish these finds in order to construct an evolutionary picture of hominid history.

Third, the consensus is always changing. Every new find, every new “species,” opens up opportunities to reinterpret the history of hominids. Again, this is not a criticism of the discipline, so much as it is an observation. The more limited the data a scientist has to draw from, the more tentative and potentially speculative her conclusions might be.

Third, the consensus is always changing. Every new find, every new “species,” opens up opportunities to reinterpret the history of hominids. Again, this is not a criticism of the discipline, so much as it is an observation. The more limited the data a scientist has to draw from, the more tentative and potentially speculative her conclusions might be.

In this context of fossils I would like to offer a thought experiment that ties both parts of this piece together. Imagine paleontologists in the very distant future, perhaps millions of years, studying the history of life on this planet. Suppose these beings were fascinated with what we know today as the dog, Canis familiaris. Let’s further suppose, based on our knowledge of the fossil record, that these dog-fossil hunters are confronted with the same limited fossil record. Given the radically variety of dogs living today, what kind of conclusions might these scientists draw?

For example, from skull remains alone, could they discern the radically different body types of a Bulldog versus a Great Dane? What kind of elaborate evolutionary  relationships would they imagine to describe the evolutionary tree of dogs? Would they conclude that some dogs are so different they couldn’t possibly have a common ancestor?

relationships would they imagine to describe the evolutionary tree of dogs? Would they conclude that some dogs are so different they couldn’t possibly have a common ancestor?

As a dog enthusiast I find the above fascinating and humorous. However, I am not trying to draw a parallel between hominid evolution and the disparity amongst dog breeds. What I want to draw attention to is the limited scientific evidence that supports neo-Darwinism. There is limited evidence that speciation has ever happened or can happen. There is a growing body of experimental evidence that changes within a species (microevolution) are limited. There is even less evidence to show how modern humans descended from some original hominid.

The next time you are confronted with the terms “species” and “speciation” I hope you will consider the possibility that these terms are not as certain or universal as many would have you believe.

[1] Taxonomy: The classification of organisms in an ordered system that indicates natural relationships. There are also examples where an additional term is added after the species. For example, modern humans are referred to as Homo sapiens sapiens to distinguish them from Homo sapiens (archaic humans).

[2] Malthus, Thomas Robert 1766-1834.

British economist who wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), arguing that population tends to increase faster than food supply, with inevitably disastrous results, unless the increase in population is checked by moral restraints or by war, famine, and disease. ( http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Malthusianism )

[3] http://www.evolutionnews.org/2012/01/talk_origins_sp055281.html. For a discussion of “ring” species, see http://www.evolutionnews.org/2012/04/sorry_ring_spec058261.html.

[4] A hominid is any ancient creature that walked on two feet.