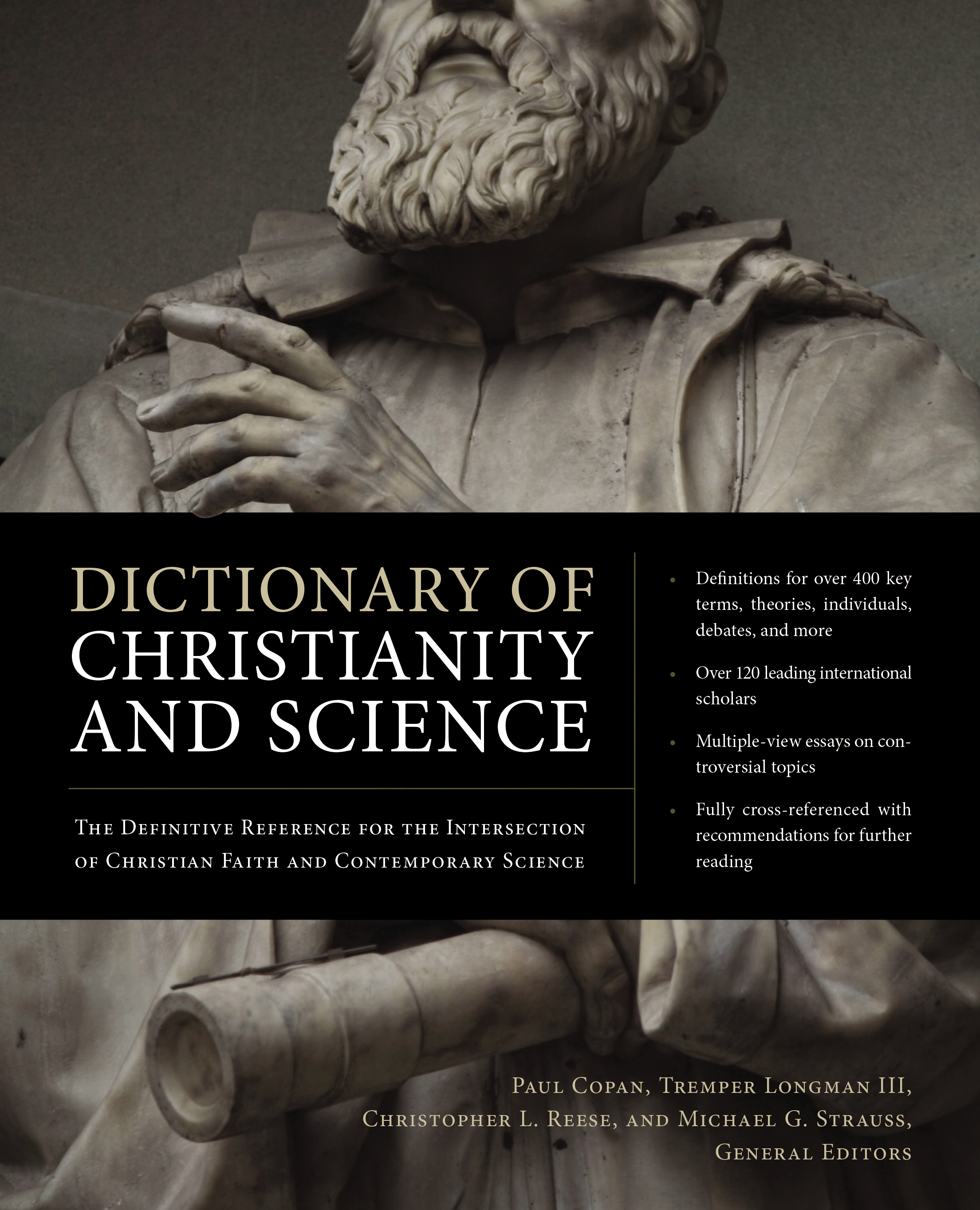

I am privileged to be one of the general editors of the upcoming Dictionary of Christianity and Science (Zondervan, April 2017). Paul Copan, Tremper Longman, Michael Strauss, and I–along with our excellent team at Zondervan–have endeavored to create a reference work that tackles the most important terms, concepts, people, and debates at the intersection of Christianity and science, from an evangelical perspective. Over the next few weeks I’ll be featuring sneak-preview excerpts from the dictionary, available exclusively here at the CAA blog.

I am privileged to be one of the general editors of the upcoming Dictionary of Christianity and Science (Zondervan, April 2017). Paul Copan, Tremper Longman, Michael Strauss, and I–along with our excellent team at Zondervan–have endeavored to create a reference work that tackles the most important terms, concepts, people, and debates at the intersection of Christianity and science, from an evangelical perspective. Over the next few weeks I’ll be featuring sneak-preview excerpts from the dictionary, available exclusively here at the CAA blog.

The first excerpt, appropriately enough, is our entry on the conflict thesis–the mistaken idea that Christianity and science are, and always have been, locked in a battle to the death where only one will emerge victorious. This canard lurks in the background of numerous discussions between Christians and atheists on the topic of science. It is a myth long dispelled by historians of science but still promulgated in popular culture. Jonathan McLatchie, the author of this piece, does a fine job deconstructing it.

CONFLICT THESIS

The conflict thesis is the overarching view on the history of science that maintains an inescapable and inherent conflict between science and religion. The most influential exponents of the conflict thesis were John William Draper (1811 – 82) and Andrew Dickson White (1832 – 1918). Draper presented a paper at the British Association meeting of 1860 on the intellectual development of Europe with relation to Darwin’s theory, just seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (Darwin 1859). It was at this meeting that the famous confrontation between Thomas Huxley and Samuel Wilberforce took place.

In the early 1870s, Draper was asked by Edward Livingston Youmans, an American popularizer of science, to write a book titled A History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (Draper 1874). Draper’s preface stated, “The history of Science is not a mere record of isolated discoveries; it is a narrative of the conflict of two contending powers, the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, and the compression arising from traditionary faith and human interests on the other.”

White published his thesis in Popular Science Monthly (White 1874), and in his book The Warfare of Science (White 1876). White further published A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (White 1896), in which he criticized what he considered to be dogmatic and restrictive forms of Christianity.

White’s perspective drew criticism from James Joseph Walsh, who argued in The Popes and Science: The History of the Papal Relations to Science during the Middle Ages and Down to Our Own Time (Walsh 1908) that White’s view was antihistorical. Walsh argued that “the story of the supposed opposition of the Church and the Popes and the ecclesiastical authorities to science in any of its branches, is founded entirely on mistaken notions” (1908, 19).

Today historians of science generally no longer favor a conflict model. Colin Russell, formerly the president of Christians in Science, criticized the conflict model, noting that “Draper takes such liberty with history, perpetuating legends as fact that he is rightly avoided today in serious historical study. The same is nearly as true of White, though his prominent apparatus of prolific footnotes may create a misleading impression of meticulous scholarship” (Russell 2000, 15).

One affair that is commonly used to support the conflict thesis is that of Galileo Galilei and his condemnation by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633 for his support of the heliocentric system of Nicolaus Copernicus. It is commonly believed that Galileo was imprisoned for his work; in truth he was placed under house arrest, and the situation was rather more complex than it is often portrayed. Also, criticisms of the heliocentric system at the time included scientific as well as philosophical and theological objections.

A study conducted on scientists at 21 universities across America revealed that the majority did not see any conflict between science and religion (Ecklund and Park, 2009). In fact, there was a correlation between those who perceived such a conflict and a limited exposure to religion. Nonetheless, there are some prominent defenders of the conflict thesis, including University of Chicago biologist Jerry Coyne (Coyne 2015) and retired University of Oxford zoologist Richard Dawkins (Dawkins 2006).

Jonathan McLatchie

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Coyne, J. A. 2015. Faith vs. Fact. New York: Viking and London: Penguin.

Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species. London: John Murray.

Dawkins, R. 2006. The God Delusion. London: Transworld.

Draper, J. W. 1874. A History of the Conflict between Religion and Science. New

York: Appleton.

Ecklund, E. H., and J. Z. Park. 2009. “Conflict between Religion and Science

among Academic Scientists?” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion

48:276 – 92.

Russell, C. A. 2000. “The Conflict of Science and Religion.” In Encyclopaedia

of the History of Science and Religion. New York: Routledge.

Walsh, J. J. 1908. The Popes and Science: The History of the Papal Relations to

Science during the Middle Ages and Down to Our Own Time. New York:

Fordham University Press.

White, A. D. 1874. ”Scientific and Industrial Education in the United States.”

Popular Science Monthly 5:170 – 91.

———. 1876. The Warfare of Science. New York: Appleton.

———. 1896. A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom.

New York: Appleton.

Taken from Dictionary of Christianity and Science by Paul Copan, Tremper Longman III,

Christopher L. Reese, and Michael G. Strauss, General Editors. Copyright © 2017 by Paul

Copan, Tremper Longman III, Christopher L. Reese, Michael G. Strauss. Used by

permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.

Pre-order the Dictionary of Christianity and Science and, for a limited time, receive $140 of bonus content.

Hello Chris! Do you know if this book will be available for purchase through logos? This would be a great resource to have in my logos library.